-Aldous Huxley

Tribute

This post is long. Substack keeps telling me to shorten it. It’s mostly images, but even if this were hundreds of thousands of words, it wouldn’t do Richard justice for the impact he’s had.

Years back, I told Richard I was working on a chess documentary. I asked if he could send me any materials he had. Shockingly, my eccentric, hermit mentor did. He mailed me a package including a thumb drive with a treasure trove of his teachings.

For us students who know he never responds to emails and messages… he read and saved them all. I like to think he read and saved them for himself, but knowing Richard, he saved them for us. He sent me copies of handwritten letters former students sent him. The letters tell how Richard changed the course of their lives.

It’s a thumb drive of his legacy– dozens of notes from former students and audio recordings of lessons. For all he has done, the least I could do is expound upon his legacy.

His students wanted his greatness to be known, but Richard remained a recluse. He should have been a guru to the world, but as Richard would say, “A career as a saint is a reprehensible goal.”

I put excerpts of notes from other students below– I’m working on a separate post summarizing the recordings I found. It’s only ~10 hours total, but he packs salient wisdom into each lesson.

Richard was irreverent. He’d constantly troll you while making clever jokes and observations that turn into philosophical discussions.

Richard was a man who never took credit. He simply gave. He loved and exalted the best ideas. His goal was for the best ideas to spread. Despite his loathing of priests, this made him the ultimate priest.

I won’t meet someone like him again. Someone who wants nothing but to contribute to the world. He was a better person than I can ever hope to become.

Below is a tribute I wrote to him, along with letters from former students.

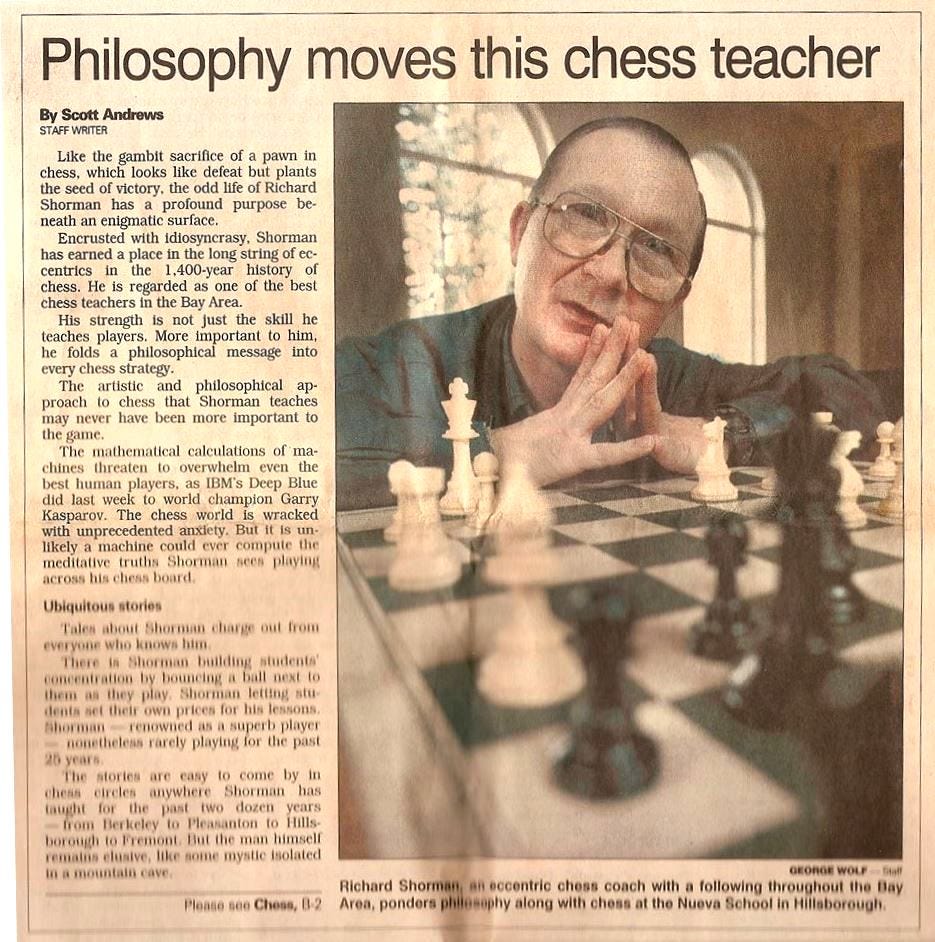

Grandmaster Shorman

My favorite teacher passed away.

His wisdom eclipsed gurus and thought leaders, but he shunned the spotlight.

As a lifelong Buddhist, he doesn’t have a family to pass down his legacy or speak on his behalf.

Richard was the first person I met who lived outside of societal norms. He did what he did because he believed it was right, sticking to his principles and values. Richard lived humbly, never caring for materials or conspicuous experiences.

He dedicated his life to others.

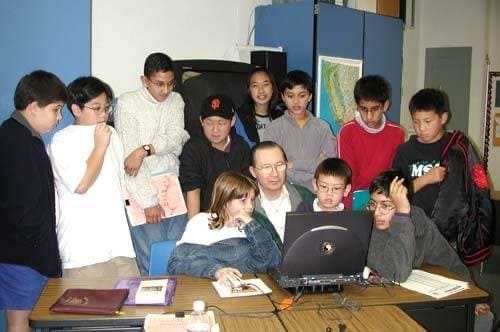

Richard handpicked his students.

He mentored generations of precocious kids to think for themselves. To lean into their creativity, to acknowledge their strengths and weaknesses.

A teacher in the purest form, he gave to the chess community and never asked for anything in return.

Literally. When he taught lessons, he never asked for compensation. He continued teaching regardless.

He piqued my curiosity.

As a kid growing up in middle-class suburbia, I found adults boring. They followed the same patterns in how they treated children.

Richard broke all the patterns while making dry, witty jokes. He showed me I didn’t have to conform to a set path.

Coincidentally, I wrote about him twice in the weeks before he died.

As a man who is hard to contact, I never got to share what I wrote with him.

I was hoping to share these the next time I saw him… but that’s not possible now.

It was a small act of appreciation for the impact he had on me. I’ll never be able to pay back the lessons he taught me on how to live an unencumbered, purposeful life.

Over time, my respect for Richard grew. He’s the only person I’ve met who had no ego. Richard lived a life of selfless service.

I’m sad he’s gone. Sad he won’t get to mentor a new generation.

I’m grateful for having the luck and honor to have been his student.

Richard nudged me to be aggressive. I became okay with chaos. Dealing with chaos became my forte. I learned to remain stoic.

I revered him.

It took over a decade for me to feel comfortable addressing him as “Richard.” We’d eat crackers and drink port, discussing chess and life. I thought that’s what adults do.

His former students describe him

What it felt like being around him:

Richard possessed a rare quality that comes only from years of personal growth – an absence of ego in conversation combined with an astonishingly sharp and lucid intellect.

Commenting on his shenanigans:

Richard Shorman tricks us all... He told me he was going to give me chess lessons then gave me life lessons instead. I'm much the better for his tricks

Essay from a former student on how Richard changed the course of their life [emphasis added]:

Mr. Shorman’s Effects

Many teachers have had a positive effect on me; one, however, stands high above the rest. Richard Shorman began teaching me chess about the time I was in the sixth grade. At first I perceived him as a quaint, eccentric old man who would go off on many tangents as he lectured. He would unexpectedly mention a great literary work and explain its significance with deep insight. Although I was initially irritated by the distractions, I would later learn to appreciate the wisdom of what he had to say. Soon our discussions would include not only chess but also school, medicine, science, and life. His brilliance as a teacher came from his ability to allow me to form correct conclusions, as opposed to merely imparting knowledge to me. Mr. Shorman repeatedly stressed the importance of paying attention, following directions, and working hard. Once a student had proven to him his willingness to do these things, he would provide him with plenty of enriching material to nurture understanding. In this way Richard Shorman helps to refine my understanding of the (Vedic) Holy Scriptures and introduces me to a wide range of disciplines, thus facilitating my growth into a mature young adult. I will be forever thankful for his excellent example of how virtue and compassion should not be restricted to church meetings and spiritual discussions, but to everyday interactions.

A Brief Introduction

Richard Shorman: a kind and virtuous mentor who has inched me along the path of light and wisdom. His tranquility and unbounded compassion are evidence of his deep knowledge and understanding of the workings of our world. Mr. Shorman remains balanced by participating in events and actions, while not being affected by them. His life of selfless service is one I would like to replicate.

Values Represented

Richard Shorman is special because he is a rare westerner who embraces deep eastern traditions. However, his skill manifests in his ability to deal with a wide range of different people; his knowledge of various cultures allows him to connect well with most any student. His values include helping others to become insightful and responsible, so that they may lead selfless and worthwhile lives. His principles are based on universally accepted truths and teachings, from which he never diverges. Although flaws are inherent in human beings’ characters, Mr. Shorman’s comes closest to being pure and unblemished.

Most Admired

Of all my influences, Richard Shorman has been by far the most inspirational. He makes me feel more than human, as if no obstacles are too large to conquer. Once Mr. Shorman stumbled upon an essay I had written and studied it carefully. Eager to receive tips on my writing skills, I questioned him about how well the work was structured. “I am not reading it,” he remarked. “I am observing your handwriting. Your use of both printed and cursive lettering signifies an inconsistent and disconnected mind. I also see that you are careless when crossing t’s and dotting i’s. These may seem trivial, but it is in the details where true mastery arises.” Seeing my shock at receiving such sudden criticism, my mentor softened and smiled. “I am not telling you about the good things in your writing. There are plenty, but how would it benefit you to know them? My goal is to make you a better person, not to flatter you with compliments.” This is a healthy attitude for teachers. They must care for the students’ long-term progress, not their short-term pleasure. Thus, although much work may make a child’s life miserable in the near future, it builds his capacity to manage stress and to think clearly, skills increasingly necessary in life. Richard Shorman does this well, but his real talent is not in the clarity with which he explains complex concepts or in his ability to make fine distinctions and discernments, but in his being a perfect model of what he preaches. He teaches others by who he is, not by what he does. His living example speaks just as cogently as his words.

--Fremont, Nov. 2005”

Another essay on how Richard changed a student’s life [emphasis added]:

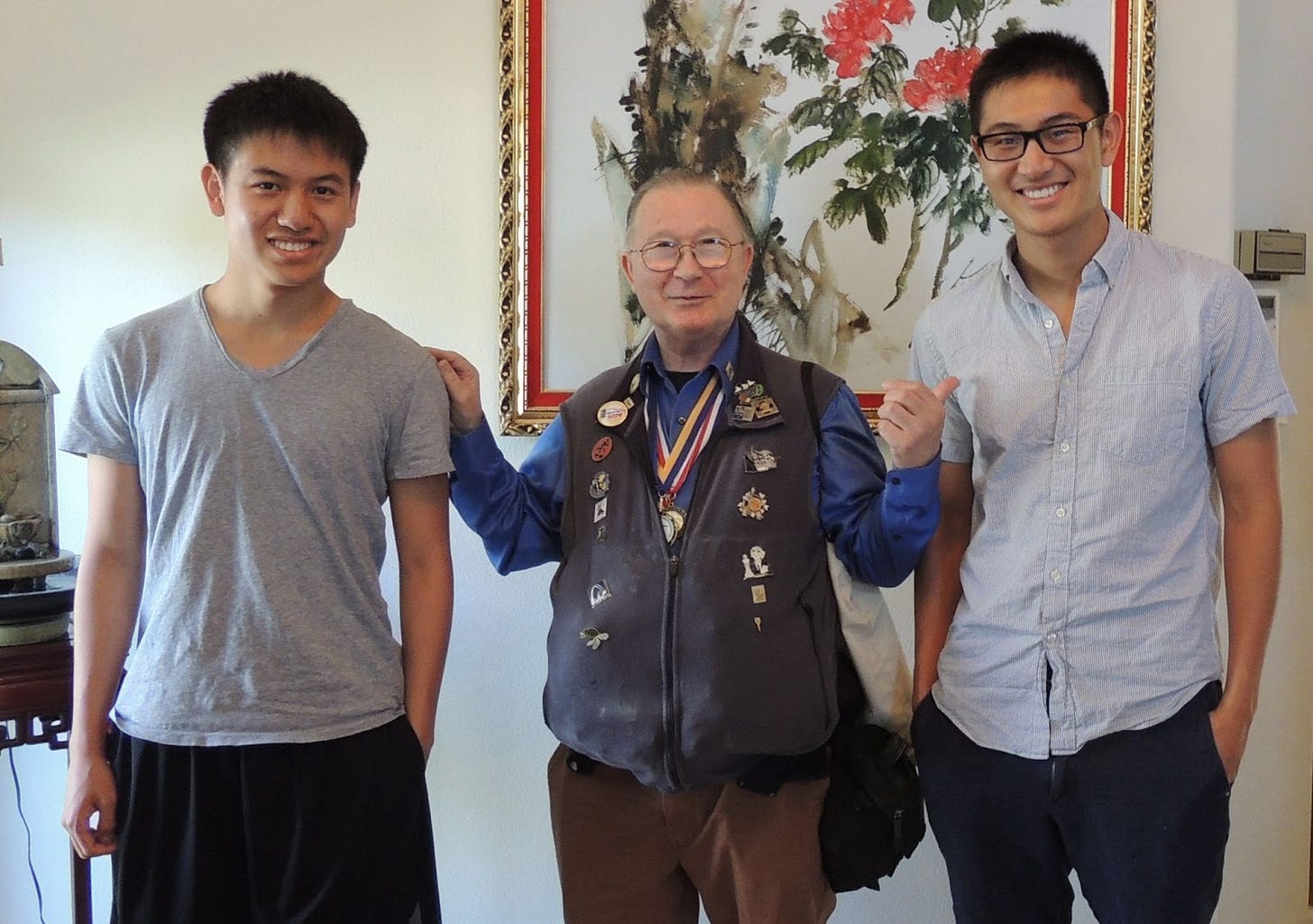

The first time Mr. Shorman came to our no-shoes-inside house to teach me chess, he told my astonished mother that he wouldn't teach without his shoes and marched right in. At the time, I was a rule-abiding third-grader, and Mr. Shorman appalled me. He wouldn't tell us his fee, saying instead to pay him whatever we thought was appropriate, and he prowled around examining the rooms for cleanliness and scrutinizing my mother's collection of Chinese calligraphy paintings. His vest, which he wore year-round, bulged with a multi-task Swiss Army knife, pictures of his students, and an assortment of pins, one of them with a picture of Yoda and the caption "May the Force Be With You." After examining our house, he accepted my mother's offer of a drink of water - but only after using a water tester he removed from his vest to check for impurities. Apparently, both the water and our house passed muster because he agreed to teach me chess.

From a chess program run through my elementary school, I learned classical opening systems like the Fried Liver and the Four Knights game and mastered basic skills like controlling the center, developing my pieces, and playing e4 as my first move. Studying with Mr. Shorman was something different entirely; I never knew what to expect.

We analyzed hundreds of chess diagrams, discussed Paul Morphy's signature - an unexpected Queen's knight move - and read Sun Tzu's The Art of War. Mr. Shorman would storm out in the middle (or at the beginning) of a lesson if he felt my preparation was inadequate. He taught me that eating before a chess game caused blood that should be in my head for thinking to instead go to my stomach for digesting, that piece development and initiative can be more important than a material advantage, and that I had nothing to fear when playing against higher-rated players. But, above all, he taught me how to take risks.

In chess, a gambit is the embodiment of risk: it involves the sacrifice of material for positional advantages. Gambits range in soundness from extremely safe to extremely risky; a risky gambit gone awry can yield too much advantage to an opponent. Mr. Shorman taught me "garbage openings" -- openings that wouldn't work against a grandmaster, but worked just fine in chess tournaments. Thanks to Mr. Shorman's encouragement to "bring up more force" in an attack, I evolved into a chess player who happily gives up measly pawns for the promise of time, space, and energy within a chess position. I yearn for the glory of creating a unique work of art through my own style, of trying to win lost games where I either triumph or die trying. And I have died trying many times.

I live in a comfortable suburb where the biggest risks are overloading on AP classes, not getting enough sleep, getting a speeding ticket, or talking to my crush. But studying with Mr. Shorman helped me find other ways to push myself, like making a fool of myself and trying freestyle rapping about biology in front of my class or pretending to know how to break dance. I refuse to acknowledge that there are limitations to what I can do. Yet, at the same time, I have learned how to take risks without being reckless (although I don't use a water filter to test my drinking water).

Now, ten years after Mr. Shorman first walked into our house and refused to take off his shoes, it occurs to me that much like Yoda did to Luke Skywalker, Mr. Shorman taught me to harness the power of the Force, to play gambits, and to take risks both on and off the chessboard. I no longer blindly trust the accepted norms; instead, I learned to trust in the Force - and in myself

A former student writes about how Richard’s lessons guided her when changing her major to music:

My most recent epiphany was brought about by a few rules that I, surprisingly, remember from about ten years back. I wanted to document it, so here it goes. (btw, tagging all Shorman students!)

I recently realized how badly my voice is out of shape. I haven't been in classical mode in a long time. Shouting along with the radio, screaming out karaoke, and hollering profanities at various Street Fighter characters have definitely not helped. Whoops.

However, now that I am definitely a music major (and relying on auditions to get into my classes) I need to get back in touch with being a serious vocalist. And you know what that means...

There's a plan of action. The way I see it, life is like chess. Once upon a time, I played a lot of chess. I even had a tutor who is, to this day, somewhat of a "chesselebrity" in the bay area: Mr. Richard Shorman. In addition to private lessons with a few close friends, I played in school clubs, library tournaments, etc. (You learn something new every day, guys!)

As you probably know, chess is guided by a set of rules. But what you may not know is that in addition to rules governing what you can and cannot do, there are also 30 short rules every Shorman student had to commit to memory that govern what you should and shouldn't do. Those rules are divided into three sections of ten rules, each section corresponding to one of the three sections of a game of chess: beginning, middle, and end games. There was a point in my life when I could recite them all in a matter of minutes... I guess that's why they stuck with me until now. For that, I am eternally grateful.

I consider this part of my life the "middle game." I'm setting up attacks to make life my bitch when the time is right, and I'm working through any problems caused by mistakes I made earlier in the game. All that jazz is the middle game. And the first rule of the middle game is to "Plan ahead." Once upon a time, I didn't pay very much attention to what all those rules actually meant, which sucks because I probably could have been a much better player if I had, but it's nice to know that they are being put to good use now. I may not be any good at chess anymore, but at least I can still use these rules to win at life.

The rules of planning, as taught to me by Mr. Shorman:

1. A plan must be suggested by some feature in the position.

What this means is that a plan should never be pulled out of your ass. There has to be some method in the madness--work with what you've got. In my case, I'm starting my music major pretty late in the game... as late as my University would allow, actually. So taking that into account, I am not going to put my focus on something I am less familiar with, such as jazz and African diaspora, experimental music, or music production. As much as I would love to study jazz, it would be much wiser of me to utilize the strong background I already have in classical performance, which would give me a clear academic advantage.

2. A plan must be based on sound strategic principles.

Plan in a way that follows the dominant paradigm of logical reasoning. "Just because" is never sufficient justification for a plan of action. Use your knights and not your bishops when in blocked pawn positions. Similarly, I'll be training with Rossini, not Rihanna. Mendelssohn, not Mariah. Bach, not Britney. Puccini, not Pink. Strategies should make sense. You get it.

3. A plan must be flexible, concrete, and short.

That means exactly what it says. Life is dynamic. Things do not tend to stay the same, and the same goes for circumstances. If the universe throws something at me that I had not accounted for in my original plan, that plan will need to evolve to accommodate those unforeseen situations.

Therefore, my plan must also be concrete. That is to say, it needs to be tangible and within an achievable range. In a game of chess, you would not plan to execute a pushed pawn ending if you have only one pawn on the second rank. Likewise, I do not aspire to be the next Maria Callas, because I lack both the raw material (talent) and the circumstances (training in a proper conservatory). But I see no fault in planning to teach or take up conducting, potentially both.

And that's as far as my plan goes. Trying to plot out my life beyond potential careers at this point is neither necessary nor practical. Everything past that point will depend upon how my plan turns out. Whether it succeeds, fails, or changes in such a way that my path has been entirely altered. Why bother wasting time on what could potentially turn out to be completely extraneous? I can plan for that when it has been suggested by some feature in the position...

I am totally going to shove chess lessons down my kids' throats. They'll be thankful when life gets complicated. I know I am.”

I published a piece on clarity of thought a day before he passed. I found this when reading another student’s eulogy of Richard:

His clarity of thought rivaled the greatest minds in history, often surpassing or rectifying their ideas. Words fail to capture the gift he was – a gift of lucidity, honesty, and wisdom.

Beyond intellect, Richard's most precious endowment was his capacity for love – genuine, selfless love. He could embrace you entirely, without reservation, accepting you as you were.

A former student writes to a committee about Richard’s selfless service:

I have never heard him express a political opinion. I have never seen or heard of him expressing an opinion, for or against, anybody.

Yet, he comes to every chess tournament in Northern California, takes thousands of pictures and saves and records the scoresheet of every game he can find, many of which make it into the chess databases and are eventually published by others.

Richard Shorman is a true volunteer

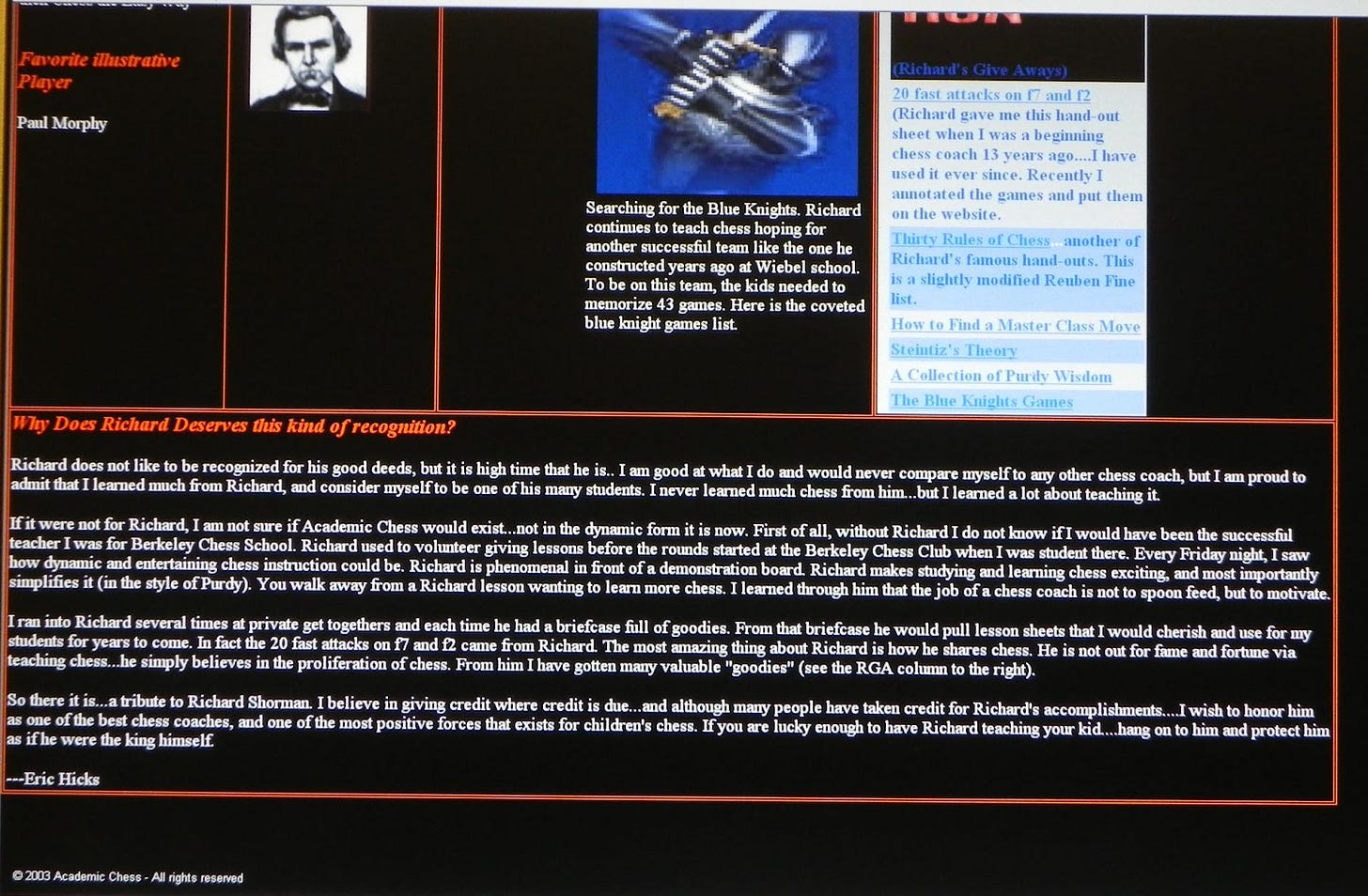

An email from a chess teacher arguing for why Richard should be publicly recognized:

Richard has taught thousands of kids in the Bay Area, and has been a chess coach for many of the main chess schools in the Bay Area, including Success Chess, Berkeley Chess School, the Mission San Jose Chess Team, and probably many others that I don’t know about. Richard has always had a non-political stance in the highly political Bay Area chess scene, and has always had unselfish motivations in promoting and teaching chess. By working with many organizations, Richard has set a fine example to many on how chess should be taught and coached to grade school kids. Richard was teaching and coaching kids using technology and exciting methods, way before the current scholastic chess craze. He inspired many future coaches and organization leaders, including myself.

Although he is rarely recognized as such, Richard is one of the best coaches in the country for grade school kids. His mentors for teaching chess include C.J.S. Purdy, Reuben Fine, and Paul Morphy. The Bay Area definitely has its share of miscreants in the scholastic chess scene...profiteers, liars, thieves, pretend chess masters, etc. etc... One thing is for sure in the wild west chess scene: Richard Shorman is definitely one of the good guys.

On improving one’s chess skills found in a Hacker News comment section:

In the late '80s and early '90s, Shorman was at the LERA chess club in Sunnyvale where each week people would bring their games and Shorman would go over them and advise them how to improve.

Shorman was particularly good at getting players who were stuck in the 1800-2200 USCF rating range moving again. One of the big reasons people get stuck is that they are trying to play too good. They are trying to apply deep positional concepts they learn from reading annotated grandmaster games, or reading books with titles like "Play Like a Grandmaster!". They are planning openings developed by grandmasters for use against grandmasters.

That's fine for grandmasters--because grandmasters UNDERSTAND what is going on. All of those deep positional concepts that shape grandmaster thought are ultimately designed to lead to a tactical advantage over their opponent, or to prevent bad tactical things from happening to them. To understand the positional stuff, you have to thoroughly understand the underlying tactics.

Shorman would steer these stuck players toward a more aggressive approach. Play the most aggressive move they can (that you can't see an outright refutation for). Open with gambits that give you a good attack.

This worked. As the stuck players got used to the sharp games that arose from this style of play, and came to really understand how the pieces worked tactically, they'd start understanding positional play, and be ready to move toward playing good chess.

The way Shorman put it was something like this (paraphrased since I can't remember it exactly): before you can play good chess, you have to get good at bad chess.

A former student sending their thanks [emphasis added]:

Greetings,

This is a thank you letter from your student, I still consider being a student of yours despite not seeing you for sometime. Anyways recently in college, I haven't had a terrible teacher in awhile until now. Upon meeting such terrible teacher, I began reflecting on my top teachers of all time (excluding family members). You have appeared up top at #1, and I think you should know that.

Without you, I'm pretty sure I wouldn't be playing chess today. I'm sure you know that there have been times where my 'burning desire for chess' has wavered. But you've been patient with my young immature/ childish self and continued educating me. Back then I never knew why learning chess from you was such a privilege. Now I know that your (what I dub as) "real" students weren't there to just learn chess from you. They were learning how to tackle problems and situations in life. Your millions of life lessons woven into your teachings of chess have not only made me a better chess player, but has made me a better person, well at least I think it did.

Even now I still question myself from time to time on whether or not I really understand your teachings. Your dedication to chess has been so valuable to many many individuals, including myself. Though you don't respond to e-mails, but hopefully you will have read this. Once again I just want to express how grateful I am to have had you as a teacher in both chess and life.

Take Care

A student comments on a typical interaction with Richard:

When Richard gave me a ride home, we parked and he gave me a little chess lesson, interspersed with Buddhism, Taoism, The Art of War, the Sutras, etc.

The most common theme, often written explicitly in the countless letters:

Mr. Shorman changed my life

Excerpt from an essay from a former student on learning to take risks [emphasis added]:

After months of analyzing my games, I discovered that I was losing because I was preoccupied with defending my king. I played conservatively--always defensive, afraid to risk. Similarly, I realized that I lived doing what was safe, fearful of the consequences. It was an epiphany: the way I lived, my fear of failure, was the true cause of decline.

Soon after this realization, I was lucky enough to meet someone who revitalized my life-- my chess coach. He forced me to work hard, and most importantly, showed me the rewards of taking risks. Though I disliked it, I soon recognized his wisdom: calculated risks are the ultimate enterprises that bring success. As I started taking more calculated risks on the chessboard, I began winning more and more games.

One day, while studying a famous chess game, I realized that this willingness to take challenges had translated to other facets of my life--I was no longer afraid of failure. Failure was the last thing on my mind when I started my school's chess club, tutored senior citizens in computer literacy, and took college classes to challenge myself.

Legacy

On her deathbed, my mom told me that you were once sick and helpless and called my parents. You had no one else. She knew I looked up to you and didn’t want me to become like you– isolated from society.

But that’s the life you wanted– removed from society. A mentor who pops in, gives sage advice and disappears to parts unknown.

When I describe you, you sound like a mythical figure. Now that you’re gone, the myth is all that remains. But you were real. A modern-day Buddha dispensing lucid wisdom.

It still feels weird calling you Richard. I called you Grandmaster Shorman for twenty years. Because that’s who you are. A grandmaster in so much more than chess. You chased your contribution and nothing else.

You were a guide and guru to all who knew you. Your former students regularly talk about you and your impact on us.

When I heard of your passing, I lost my composure. It was the first time in years. Ironic as you’re the one who taught me to be stoic. Guess I’m still learning…

Thank you for everything.

RIP Richard “Grandmaster” Shorman (1938 - 2023)